HISTÓRIA

"ESCALADAS A SUL DO CABO DA ROCA" UMA BREVE HISTÓRIA

excerto de ESCALADAS A SUL DO CABO DA ROCA de Paulo Roxo, início dos anos 2000

Para um escalador de espírito aventureiro é fácil imaginar uma miríade de vias a cruzar as falésias de granito que constituem toda a região costeira a sul do Cabo da Roca. No entanto, apesar do enorme potencial desta faixa de falésias, só o sector do ESPINHAÇO chamaria, até muito recentemente, a atenção dos escaladores. Este fenómeno talvez tenha a ver com a própria história da escalada em Portugal.

No início dos anos 80, os escaladores do País constituíam apenas uma pequena "tribo" selecionada, condicionando o número de aberturas. Por outro lado, o advento da escalada desportiva rapidamente contribuiu para desviar as atenções de grande parte da nova geração na direção de uma atividade geralmente mais "acessível", em contraponto com a mais complicada escalada clássica.

Assim, não é de estranhar que o Espinhaço tenha, de certa forma, bastado para preencher os desejos de "conquista" dos "clássicos" do momento. Por acrescento, esta parede foi durante muitos anos o marco mais representativo da escalada tradicional de dificuldade nos arredores da grande Lisboa.

Os seus impressionantes tetos e o infame filão de rocha cinzenta decomposta, que cruza toda a parede, ajudaram a criar sobre este local uma aura de inegável carisma.

Das cinco zonas principais apresentadas neste guia, o Espinhaço representa a mais alta e também a mais "antiga". A via "Normal" foi a primeira a ser aberta. Paulo Alves e Carlos Teixeira formaram a cordada que, após algumas "investidas" anteriores, completou este itinerário. Estávamos em 19 de Agosto de 1981.

A febre de entusiasmo que se propagou pelos escaladores desta época, culminou em 20 e 21 de Maio de 1989 com a realização de um encontro nacional de escalada. Como pretexto para este encontro foram reequipadas algumas reuniões e passagens mais expostas das vias abertas até então.

A passos lentos a história foi-se moldando com a abertura de novas vias. Quase todas as linhas completas até ao topo da falésia foram realizadas "à custa" dos estribos, como peças fundamentais para cruzar os tetos pronunciados. No entanto, em Maio de 90 surge a primeira exceção, com a abertura da via "Lunática"", pelas mãos (e pés) de Francisco Silva e Paulo Gorjão. Desde a sua fase de projeto, este é um itinerário pensado para a escalada livre. Portanto, o seu nível técnico, que ronda o 7a, acabou por tornar este itinerário numa referência de dificuldade, ainda hoje reservada a escaladores de alto nível.

Com uma filosofia absolutamente diferenciada da escalada livre, surge, em dias mais recentes, a "Cuba Livre". Com uma clara inspiração nas técnicas de big wall, esta via de três largos, completa em 9 de Janeiro de 98, por Ricardo Nogueira e, com a minha participação na abertura do 2º largo, representa (até à data de realização deste guia), o expoente máximo da escalada artificial de toda a região (A3+/A4 -pela exposição-, 3° largo).

Como apontamento de destaque, torna-se interessante referir que primeira repetição desta via foi levada a cabo por Francisco Ataíde em solitário, confirmando o elevado nível psicológico deste escalador de elite.

Hoje em dia, a escalada no Espinhaço encontra-se um pouco "assombrada" pelo elevado estado de degradação do equipamento fixo[i]. Devido à ação conjunta do mar e do vento -elementos bastante ativos por estas paragens- todos os pitons e muitos spits estão transformados em verdadeiras bombas relógio. Felizmente, muitas passagens podem ser reforçadas mediante a utilização de friends ou entaladores, possibilitando desta forma a realização, mais ou menos segura, de todas as vias existentes.

Em comparação com o período temporal que consolidou a história do Espinhaço, o período correspondente às restantes quatro zonas referidas neste guia têm uma cronologia muito mais recente e encadeada. Os primeiros passos da "nova vaga" ficam, em parte, a dever-se a João Dinis, escalador da região que, durante uma caminhada "descobriu" a Baía da PONTA ATLÂNTICA. A visão da "Parede das Tormentas" bastou para o motivar a efetuar uma nova visita, com o fim de abrir novas vias de escalada. Em breve surgiam os primeiros itinerários. A via do "Diedro" e a do "Canal" apareceram nos intervalos que, parcialmente, interrompiam a abertura da maior das três primeiras linhas: a "Cabo das Tormentas". Com três largos de comprimento, esta resulta numa das mais interessantes vias da zona. Com efeito, o seu atrativo segundo largo, constituído por uma lastra fortemente extra-prumada, originalmente cotado de A1+, foi forçado em livre e, à vista, por Francisco Ataíde durante a primeira repetição desta via, em Setembro de 98. O seu grau foi, desde então, transformado em 7a (duro).

Inspirado pelas recentes realizações de João Dinis e, despertando para a perspetiva do excelente potencial de escalada ainda por descobrir, comecei, em conjunto com Yolanda, a explorar uma "nova" zona. Juntos, abrimos a maioria das vias existentes na BAÍA DOS NAUFRAGOS. O destaque vai para o sector da "Esquina do vento" cujas vias centrais partem de uma original travessia no interior de um canal natural por onde entra o mar. Um apontamento curioso para a existência de um corredor de vento Que assola constantemente o ponto exato de início da via "O silêncio dos teus olhos”, numa área formada apenas por alguns metros quadrados.

Uma segunda marcha de busca, numa soleada manhã de domingo, levou-me a explorar a região da BAÍA DAS QUATRO PEDRAS. A principal opção consistia numa placa tombada e de aparência monótona que se avistava desde o cimo desta baía.

O interesse suscitado era escasso assim que, após contornar esta placa pelo seu topo e descer até à ponta do caótico esporão de blocos, dei de caras com uma bonita parede, situada do outro lado da baía e virada ao mar, longe dos olhares de escaladores "aberturistas" de outros tempos (existe a referência verbal de uma anterior visita em top rope). Passei imediatamente a palavra desta recente "descoberta" e, não tardou mais de uma semana para, em conjunto com Vitor Viana (outro entusiasta da região), realizar uma visitinha ao local, munidos, como é evidente, de toda a quinquilharia de friends e entaladores. A abertura inicial das "À primeira dói mais" e "Pirataria Desportiva" cederam passo às outras 12 vias que convivem hoje em dia neste sector, nomeado: "Promontório".

Um pouco depois da atividade quase cirúrgica levada a cabo no Promontório, resolvi dar uma vista de olhos à placa de "aparência monótona" referida anteriormente, situada no interior da Baía das Quatro Pedras. Destrepando a enorme cascalheira de grandes blocos, em breve cheguei à base da parede. A visão obtida desde aqui nada tinha de monótona e, a facilidade transmitida era puramente ilusória. Assim, numa sequência quase perfeita o sector do "Lobo mau" viu cair os itinerários até ao número sete. Pelas características da parede, as suas dificuldades abrangem, sobretudo, problemas técnicos de continuidade, em graus que variam entre o V+ e o 6c+. Através de um investimento levado a cabo por um pequeno grupo de escaladores assíduos, foi comprado material em inox para equipar as vias abertas de três zonas de exploração mais recente.

Salvaguardando a filosofia própria do local, claramente instaurada pelos primeiros escaladores que centraram os seus esforços na região do Cabo da Roca, o equipamento fixo foi a opção adotada apenas para alguns pontos de proteção impossível, máxima exposição ou relés. As poucas vias totalmente equipadas constituem neste caso, a exceção à regra, muito embora, sejam belas exceções como a "És muita linda (7c+)", a "Equinox (7a)", a "Pirolita (7c+)" e um curto etc.

Ainda existe novo terreno por explorar na região do Cabo da Roca. E a prova está na "descoberta" de um novo sector em princípios de 2000: a BAÍA ESTREITA onde existem várias possibilidades. No entanto, o relevo poderá ir, muito em breve, para a repetição de algumas das mais duras vias já estabelecidas, bem como, para a realização "em livre" de linhas tradicionais de artificial (em especial no Espinhaço). Muito provavelmente a história irá ser escrita por estes três fatores juntos.

Mas uma coisa é certa: todas as vias reunidas neste guia, em conjunto com as restantes "errantes", irão ficar para as futuras gerações como um legado indelével de uma região de carácter único.

[i] Atualmente (2025) as vias mais “frequentadas” do Espinhaço foram já reequipadas e não se correm os riscos mencionados neste texto.

ESCALADAS NA PRAIA DA URSA NAS DÉCADAS DE 1960 E 1970: A URSA, A NOIVA E AS OUTRAS

Textos e relatos de Santos Vieira, Alexandre L. Garcia e Rogério Morais -

excerto do GUIA DE ESCALADA DE LISBOA

A década de 60 foi fértil na descoberta que a juventude portuguesa fez do meio desportivo e de ar livre, um pouco à semelhança da restante europa,

mas com uma dinâmica totalmente em diferido, fruto do total alheamento que até aí se verificou face a estas atividades e a um notável isolamento de Portugal face ao restante continente europeu. O atraso era de décadas, mas tentou recuperar conceitos e importar o que era possível (as ideias livres e o material sofisticado).

Foi assim que a espeleologia e o montanhismo nasceram no seio do movimento campista, também ele formado por um grupo de entusiastas que lutaram para que o movimento campista fosse reconhecido e legalizado. Recuemos ainda outros 20 anos: o Clube de Campismo de Lisboa foi fundado em 1941; o Clube Nacional de Montanhismo fundado em 1943 (Porto); a Sociedade Portuguesa de Espeleologia em 1948. A secção do sul do CNM autonomizou-se em 1958 e passou a desempenhar então o ponto de reunião para organizar as saídas de escalada da região de Lisboa.

Foram os seus dinamizadores um conjunto de jovens saídos dos três clubes acima mencionados. Os mais ativos na escalada em rocha, a par do mais alargado montanhismo, eram o guia Lázaro e o filho (formados no CNM do Porto), Daniel Crespo, José Avellar, Américo Condinho (um virtuoso da construção de material de espeleo, um verdadeiro Senhor Petzl português), Armando Cardoso, José Ferrer, José Ilídio, Maldonado e uns recém-chegados, Júlio Valente, Luís Filipe Baptista e Santos Vieira.

Escalavam sobretudo na Arrábida, Sintra e Montejunto. A estética era mais importante que o grau, mera tabela internacional que ajudava um pouco a enquadrar as atividades. O material de escalada era caro, raro de encontrar nas escassas lojas desportivas, e isto limitava bastante o acesso a novas vias, e sobretudo a novas técnicas de escalada. Outro virtuoso da “manufatura” de material de escalada, Carlos Santos Vieira, tinha acesso a uma oficina metalúrgica de grande qualidade, e começou a fabricar pitons de várias dimensões, cunhas, estribos e martelos, o que proporcionou mais alguns “voos” extra.

A Ursa

Textos e relatos de Santos Vieira, Alexandre L. Garcia e Rogério Morais -

excerto do GUIA DE ESCALADA DE LISBOA

Numa das marchas de fim-de-semana para o Cabo da Roca, o grupo dos mais novos e irreverentes foram acampar na praia da Ursa e era impossível, para escaladores nos seus vigorosos vinte anos, não sonhar com a escalada destes rochedos, em particular a mais afilada Ursa. Começaram de imediato a planear a sua escalada.

No seu caderno de apontamentos, Carlos Santos Vieira registou a data de Março de 65, em que a viu pela primeira vez. A face sul, virada para o Cabo da Roca, pareceu-lhes demasiado ambiciosa e a exigir material de que não dispunham. Decidiram trazer binóculos na saída seguinte, para explorar, da encosta fronteira, a face leste, virada a terra. Estudaram também as marés e meios de vir para terra caso a descida fosse realizada com a maré cheia. Nessa altura a passagem entre a Ursa e terra era bastante funda e com a maré cheia e ondulação, tornava-se bastante difícil de atravessar. O resto desse ano de 1965 foi febril a arranjar mais pitons, cunhas de madeira e cordas. O Ferrer tinha adquirido uma corda dinâmica de nylon de oito milímetros, com sessenta metros, santos Vieira tinha uma corda de cânhamo branco de nove milímetros com setenta metros que lhe tinham trazido de França. Acordaram também em levar uma corda de algodão de doze milímetros com quarenta metros para o caso de terem de instalar uma tirolesa para passar a maré alta.

O José Ilídio, um dos mais aptos escaladores da Secção Sul do CNM, tinha ido entretanto para o serviço militar obrigatório, pelo que outro virtuoso de Lisboa, o Luís Filipe Baptista decidiu organizar uma cordada com ele como “primeiro”, o Carlos Santos Vieira e o Júlio Valente.

No dia 7 de Fevereiro de 1966, cerca de um ano depois de terem iniciado o planeamento da escalada, saíram de madrugada da Casa Abrigo dos Capuchos, então gerida pelo CCL, carregados de material. Eram cinco horas da manhã quando chegam à base da Ursa, com maré vazia. Como não sabiam a hora da descida, deixaram montada uma tirolesa com a corda de algodão, montada entre a escada dos pescadores e o rochedo que fica no sopé da Ursa para permitir a retirada mesmo com a maré cheia, nesta época alterosa no canal.

A rocha desde os primeiros passos revelou-se muito friável, desfazendo-se na maior parte das presas e dificultando grandemente a pitonagem dos pontos de proteção. Apesar de ser calcário, este é muito metamorfizado, isto é, foi atravessado por um filão eruptivo que o transformou e tornou mais friável, cristalino, e com fendas que quando eram pitonadas, se fragmentavam ou desfaziam.

Grande parte da escalada foi por isso ocupada a limpar e a desprender fragmentos de rocha. Levaram capacetes comuns de construção civil, que se revelaram muito úteis para a constante chuva de pedras que constantemente se desprendiam da parede.

A meio da subida, já passado o diedro em “V”, notaram a movimentação de alguns companheiros que tinham chegado à encosta fronteira à Ursa, entre os quais o Armando Cardoso, autor da foto do inicio desta página (cume da Ursa, 7/02/1966).

A escalada prosseguia lenta e morosa, a tarde de inverno caía rápidamente e o Luís Filipe tomou a decisão de pedir ao Júlio Valente para ficar numa reunião abaixo do cume para pelo menos tentarem sair ainda com luz. Eram cerca de 16.00 horas, e o pôr-do-sol espectável logo pelas 17.30.

Decisão difícil, mas que permitiu chegar ao cume, mal equilibrados em rocha muito fragmentada, posaram para a foto que sabiam que o Cardoso não deixaria de fazer, com ele e os restantes companheiros a acenarem-nos de terra. Cravaram numa fenda mais exposta uma moeda de um escudo de 1966, para assinalar o evento e deixaram a marca que seria repetida por muitos escaladores nas décadas seguintes. Procuraram depois o melhor local para cravar dois pitons “U”, montaram um top com várias cordeletas e desceram em rapel pela face nordeste ao encontro do Júlio. Daí e após recuperação da corda desceram o diedro e a parte terminal, sempre em rapel e com a segurança da corda de cânhamo. Saíram para a base e conseguiram passar já com a maré vazia de, depois de cerca de catorze horas nesta primeira escalada da Ursa.

Outro relato da primeira ascensão da Ursa

Relato de Carlos Santos Vieira

A década de 1960 foi fértil em acontecimentos que criaram na juventude da época um forte espírito de protesto/oposição,

A seção sul do CNM foi inaugurada por volta de 1958 e tornou-se o ponto de encontro para o planejamento de viagens de escalada.

A sua força motriz foi um grupo de jovens escaladores como o guia Lázaro e o seu filho, formado no CNM do Porto, Daniel Crespo, José Avellar, Américo Condinho, Armando Cardoso, José Ferrer, José Ilídio, Maldonado, e alguns recém-chegados, Júlio Valente, Luís Filipe e Santos Vieira. Subimos na Arrábida, Sintra e Montejunto.

Os equipamentos de escalada eram caros e difíceis de encontrar em lojas de artigos esportivos, o que limitava bastante o acesso a novas vias de escalada. Como eu tinha acesso a uma oficina metalúrgica de alta qualidade, comecei a fabricar pitons de vários tamanhos, cunhas, estribos e martelos, o que nos permitiu fazer mais alguns lances de corda.

Num fim de semana de passeio, acampamos na Praia da Ursa. Anotei no meu caderno a data de março de 1965, quando a vi pela primeira vez. A face sul parecia-nos demasiado ambiciosa e exigia equipamento que não tínhamos. Decidimos levar binóculos (emprestados, claro) para explorar a face leste a partir da encosta oposta.

Em outro fim de semana, fizemos exatamente isso e concluímos que era viável com o equipamento que tínhamos e o que estávamos nos preparando para fabricar. Também estudamos as marés e os meios de retornar à costa caso a maré estivesse cheia. Naquela época, a passagem entre Ursa e o continente era bastante profunda e, com maré alta e ondas fortes, era muito difícil atravessá-la.

Aquele ano foi febril, dedicado à aquisição de mais pitons, cunhas e cordas. Ferrer havia comprado uma corda de náilon dinâmica, com oito milímetros de espessura e sessenta metros de comprimento, e eu tinha uma corda de cânhamo de nove milímetros e setenta metros que me fora trazida da França. Também combinamos de levar uma corda de algodão de doze milímetros e quarenta metros de comprimento, caso precisássemos improvisar uma tirolesa para atravessar na maré alta. Luís Filipe decidiu organizar uma expedição de escalada com ele, eu (Santos Vieira) e Júlio Valente.

Em 7 de fevereiro de 1966, cerca de um ano depois de termos planejado a escalada, partimos da Casa Abrigo dos Capuchos, então pertencente ao CCL, carregados com o equipamento. Eram cinco da manhã quando chegamos à base do Ursa. A maré estava baixa, mas como não sabíamos a que horas desceríamos, deixamos uma tirolesa armada com a corda de algodão, estendida entre a escada de pescador e a rocha ao pé do Ursa, para nos resgatar caso descêssemos na maré alta.

Desde os primeiros movimentos, a rocha mostrou-se muito friável, esfarelando-se na maioria das agarras e tornando a colocação de pitons para proteção extremamente difícil. Grande parte da escalada foi, portanto, gasta limpando e quebrando fragmentos de rocha que bloqueavam as agarras. Tínhamos levado capacetes de construção comuns, cujas abas cortamos e às quais prendemos jugulares; eles se mostraram muito úteis contra a chuva constante de pedras que se desprendiam da parede.

A meio caminho, depois do diedro em “V”, notámos alguma movimentação de companheiros que tinham chegado à encosta oposta à Ursa, entre eles Armando Cardoso, o autor da fotografia do cume aqui apresentada. A subida prosseguiu lenta e laboriosa; a tarde de inverno desvanecia-se rapidamente, e Luís Filipe decidiu pedir a Júlio que ficasse cerca de três lances de cordada abaixo do cume, para que ao menos pudéssemos tentar chegar ao topo enquanto ainda havia luz. Provavelmente eram cerca de 16h00, a julgar pelo ângulo do sol, com o pôr do sol previsto para as 17h30.

Foi uma decisão difícil, mas permitiu-nos, depois de mais alguns lances de corda, chegar ao cume. Mal equilibrados em rocha extremamente fragmentada e instável, posámos ali para a fotografia que sabíamos que Cardoso não perderia, com ele e os outros a acenarem para nós lá de baixo. Cravámos numa fenda exposta uma moeda de um escudo de 1966 para assinalar o evento e deixar prova da nossa passagem. Depois procurámos o melhor local para cravar dois pitões em “U”, montámos uma ancoragem com várias fitas e descêmos de rapel pela face nordeste para encontrar o Júlio. Dali, e depois de recuperarmos a corda, descemos o diedro e a secção final, sempre de rapel e com a segurança adicional da corda de cânhamo.

Chegamos à base e conseguimos atravessar justamente quando a maré estava subindo novamente. Assim, completamos cerca de quatorze horas nesta primeira ascensão ao Monte Ursa.

A Noiva

Subiram equipando a via com pitons, que a segunda cordada desequipava. Quando o escasso material acabava, esperavam a chegada do último para passar o material recuperado para o primeiro.

Na tentativa de subir o mais direto possível a parede, veio a revelar-se necessário retroceder e passar um pouco para a esquerda na horizontal, aproximando mais da vertical do rapel. Na linha mais direta, a rocha apresentava-se cada vez mais insegura (por essa razão esta via viria a ser abandonada daí a 4 ou 5 anos, em detrimento da Face Sul).

Passaram 9h30m na parede, e se não tivesse ficado registado na caderneta de escaladas já não acreditariam posteriormente nesse longo horário. Anotaram ainda no caderno do Alexandre: “Nota: Muito perigoso pelas pedras soltas”. Das lembranças que lhes restam, não existiu medo nem dúvidas relevantes, apenas o som do vento, e o magnífico ruído dos pitons cantando, acompanhado do cheiro a enxofre rocha martelada.

As duas fotos de cume estiveram perdidas por vários anos, e chegou a publicar-se que as primeiras escaladas da Noiva datavam de 1975 (até ser difundida a foto no cume). Uma das fotos (foto acima deste parágrafo, perdida ainda mais um par de anos) mostra o detalhe da preparação da descida, com o Alexandre a martelar o piton do rapel de descida, um único piton que levaria depois uma cordeleta para permitir a recuperação da corda. Esse piton ficou como única marca física dessa conquista. Perda sentida pela cordada, pela dificuldade que era conseguir material bom.

Os primeiros encordamentos do grupo, que viria posteriormente a escalar a Noiva pela primeira vez, verificaram-se precisamente na espeleologia das BEC’s e datam de setembro de 1970, com o Alexandre Lugtenburg de Garcia e o Américo Abreu. Em janeiro do ano seguinte já tinham alargado as suas atividades para o montanhismo (Penedo dos Ovos, em foto de 10 de janeiro de 1970) num curso básico de montanhismo.

Ambos escalaram ainda nesse verão de 1971 com o António Nunes Morais e o Gaspar Dias. Estava formada a cordada que viria a conquistar a Noiva.

Conheceram a Ursa e a Noiva em 15 de setembro de 1971, numa incursão rápida à Pedra Nova, e retornaram dia 26 de setembro, após três dias de escalada na Serra da Estrela, para escalar a Ursa, aberta ao pequeno mundo da escalada portuguesa 5 anos antes, conforme descrito acima.

Voltaram no dia 4 de outubro para “Prospecção e observação das paredes da Noiva”, mas logo no dia seguinte, 5 de outubro de 1971 lançaram o ataque definitivo à “impressionante” Noiva, na época também conhecida como Ursa do Norte.

Sem muita discussão, tinham tomado a opção pela parede que dava para o continente (aquela por onde discorre o atual rapel) aparentemente mais direita e acessível que as opções mais tortuosas da face sul, com o seu corrimão e sucessivas mudanças de prumo.

Partiram cedo e pouco carregados. Apenas o Morais carregou uma pequena mochila. A via revelou-se perigosa pela rocha instável, com muita pedra solta. Houve uma passagem em que uma pedra de uns 15 quilos se soltou com o Alexandre, com todos os outros a terem de se colar á parede para sobreviver.

Pendurados na cintura, apenas um martelo, alguns pitons e mosquetões, material precioso adquirido no parisiense Vieux Campeur. Fitas ainda não estavam disponíveis. O encordamento era na cintura, o arnês de fita só viria a aparecer mais tarde, após o curso do Alphonse Darbellay em Portugal, e apenas o Abreu usava capacete.

Inicialmente formaram duas cordadas, que viriam a juntar numa só na fase final da parede:

-

Alexandre Lugtenburg de Garcia e Américo Abreu Rodrigues

-

Gaspar Dias e António Nunes Morais

Entretanto, a par do núcleo muito ativo do CNM Sul, uns quantos jovens (ainda mais jovens!) evoluíam nas BEC’s (Brigadas Especiais de Campo, enquadradas pela Mocidade Portuguesa, mas com pouco ou nenhum cunho político). Além da escalada e montanhismo, destacavam-se sobretudo na espeleologia, modalidade com um cariz também científico (a SPE tinha sido já fundada em 1948, como vimos, e a modalidade tinha atingido em Portugal a maioridade), a par do mergulho, pilotagem, planadores e até paraquedismo, tudo modalidades consideradas “radicais” na época.

Espinhaço

Breve crónica da escalada tradicional no Espinhaço de Filipe Costa e Silva

Aqui é o Cabo da Roca! Aqui é o Cabo da Roca! É o que repete o vento, redemoinhando sobre a costa. É aqui que o horizonte não cabe inteiro no olhar, que o Ocidente toma o seu outro nome de Poente e a infinita distância promete o que só em sonho se pode cumprir. Um lugar de fronteira, por vezes em caos e por vezes em paz. Um lugar como não há outro, onde o mar tenha tanto de mar, o céu tanto de céu e entre eles penhascos de granito dourado.

Por um caminho sempre a descer chega-se às ruínas do forte do Espinhaço. Mas o que hoje são apenas troços das muralhas e um resto do tecto abobadado do paiol, foi outrora um altivo forte que pertencia ao sistema defensivo da barra do Tejo.

Edificado em meados do séc. XVII (a primeira planta do fortim data de 1693) manteve-se artilhado até 1831, ano em que foi desactivado e lhe retiraram os canhões de ferro e de bronze, os mosquetes e arcabuzes, os quintais de pólvora, os cartuxos e os pelouros.

A partir dessa data, à mercê das chuvas e ventos da agreste costa, foi decaindo, pedra a pedra, até que um dia do ano já perdido de 1978 vieram uns escaladores descobrir a parede abrupta sobre a qual se ergue o forte...

Velhas e novas conquistas

Apesar de ter apenas uns 100 m de desnível a parede do Espinhaço tem uma grandeza própria que lhe empresta o mar e que torna a escalada especial.

Para além dos dias perfeitos, frios e de aderência como lixa, rocha a parecer ouro, com um mar tranquilo e céu limpo, há também os outros dias, os mais habituais… Esses, são os dias de Sol abrasador ou os dias cinzentos com uma omnipresente humidade, devoradora de magnésio, que nos causa suores frios enquanto uma mão escolhe um friend e a outra vai escorregando na presa. E como pano de fundo um mar sempre a rugir lá no fundo e a intimidar-nos, quando ainda mal saímos da reunião e já deixamos de ouvir o assegurador para só ouvir essa máquina de lavar gigante. Mas ainda assim a escalada no Espinhaço deixa-nos sempre boas sensações e muitas das vias são autênticos tesouros por descobrir.

A primeira conquista do Espinhaço, esse privilégio único e irrepetível, coube aos escaladores Paulo Alves e Carlos Teixeira no ano de 1981. Após duas tentativas anteriores, foi a 19 de Setembro desse ano que estes dois escaladores, com um jogo sortido de 18 pitons, um jogo de entaladores e já com um ou dois friends, terminam em 9 horas e meia a via Normal. Vale a pena, como registo histórico, reportarmo-nos às notas do Paulo Alves sobre a via: “A parte mais delicada da via, em geral muito bonita, é o 3º largo de artificial com maus pitons, bastante aérea, em subprumo para a esquerda. Quatro pitons já lá tínhamos deixado e pus mais 8; duas passagens usando o friend nº 3”.

Em três horas estava feito esse largo chave e ouvia-se o martelar de dois bong-bongs na reunião. Para o topo da parede faltava agora apenas uma trepada fácil de III grau. Estava vencida a parede e iniciava-se assim uma década de conquistas.

Estas aberturas foram resultado do esforço de muitos escaladores que iam forçando o caminho aos poucos, piton a piton, estribo a estribo, medo a medo, largo a largo, de aventura em aventura, às vezes demorando a conquista de uma via mais de um ano de tentativas dispersas de diferentes cordadas. Do grupo de escaladores mais activos fizeram parte, entre outros, Jorge Matos, Vasco Pedroso, Carlos Teixeira, Henrique Cabreira, José Luís Carvalho, Nuno Pardal, Luís Fernandes, Francisco Silva e José Pereira.

De entre todos, destaca-se o P. Alves, presente quase sempre em todas as tentativas ou aberturas de vias, que hoje em dia são literalmente as clássicas das clássicas. Como a impressionante Transatlântica aberta em 1987 com J. Matos. Uma espécie de Titanic das vias, que merece bem o nome por cruzar grande parte da parede, num ambiente de viagem sobre o mar e com muito boas sensações de naufrágio eminente, que ainda hoje em dia impõe respeito. Aliás, esta via deveria ser considerada como uma visita a um museu de arte da escalada, onde é possível encontrar não só os costumeiros pitons e spits de oito, mas também as elaboradas cunhas de madeira de oliveira e cerejeira, entaladas nas grandes fissuras. Toda uma via que à medida que escalamos por ela e imaginamos os primeiros a fazê-la, nos ensina a tirar o chapéu!

Em outubro de 1989 Paulo Gorjão escalaria em livre a Imaginária (7a) marcando a introdução nesta parede da escalada livre de dificuldade, anunciando-se um novo tempo, o da exigência de uma maior forma física e técnica de escalada.

A iniciar a década de 90, F. Silva abre por cima a via Lunática (6c) e encadeia em livre. Já não se trata apenas de conquistar e de vencer a parede, mas de mudar o objectivo para a forma como se escala. Contra a corrente desta tendência “em livre” destaca-se a abertura em 1996 da via Heróis da BD (A3) por João Schiappa e José C. Sousa, e mais tarde em 1998, da via Cuba Livre (A4) por Ricardo Nogueira e Paulo Roxo, que seria repetida em solitário no mesmo ano pelo Francisco Ataíde.

Com a entrada do novo Milénio as vias de artificial têm os seus dias contados. Os escaladores que agora vêm experimentar as velhas vias trazem novas palavras no cérebro: em livre, dificuldade, encadear. Em 2001, o F. Ataíde semi-equipa a via Tomatada (8a+) que saindo do 2º largo da Transatlântica aponta a direito para a proa mais estética da parede, um sólido e liso extraprumo que se revelaria um osso bem duro de roer (encadeado em 2005 por F. Ataíde).

Desta nova mentalidade e das possibilidades que os novos materiais de protecção oferecem, abrem-se vias totalmente em auto-protecção como as atrevidas “Telefuncken (7a+)”, a “Cavalgar o Tigre (7c)” ou a “Esta via não é para velhos (7c)”, verdadeiras pérolas clássicas. Para esta nova geração é a descoberta da verdadeira beleza da escalada clássica: a progressão limpa e o desafio da auto-protecção, onde mais do que conquistar, mais do que a dificuldade e conseguir encadear, existe uma forma ética e estética de escalar que é indissociável do próprio jogo da clássica.

Presente e futuro

As velhas vias libertadas, a Tomatada encadeada e repetida, o Tigre cavalgado e domado… Não sobram desafios no Espinhaço?

Pelo contrário, cada pequeno triunfo abre novas perspectivas e ensina o olhar a procurar novos limites. Ajudados pela constante evolução do material de auto-protecção, a barreira do impossível retrocede vários passos e onde outrora era preciso passar medo, bolas de aço e protecções de chumbo, agora apenas é preciso dois ou três novos micro-friends. Uma específica mas das melhores sensações destes desafios é aquele misto de dúvida e optimismo da possibilidade ou não de fazer em livre uma via de artificial. Experimentar com alguma ansiedade os friends nos buracos mais raros, todos os tamanhos de entaladores na fenda que os cospe, calcular percentagens mentais entre o “à bomba” e o “mero enfeite” e no fim decidir pela positiva e aceitar os incertos riscos. Assim, se por um lado algumas velhas vias terroríficas passam a ser um passeio no parque, os horizontes que se abrem prometem novos desafios para o futuro, porque é preciso ter sempre pelo menos uma linha para sonharmos com ela ou para não nos deixar dormir.

A escalada clássica é sem dúvida o terreno da liberdade. E são os escaladores que devem salvaguardar o seu próprio futuro, não cometendo o pecado mortal do Cesare Maestri, e deixar espaço para os grandes sonhadores, para aqueles que precisam da liberdade absoluta, da rocha vazia, espaço para o impossível de hoje. Que tristeza maior pode haver, para quem procura escapar à lógica limitada da escalada desportiva, do que chegar a uma parede e ver chapas desnecessárias por todo o lado? Vias sinalizadas como ruas urbanas, balizadas com chapas a piscar ao sol e a indicar por onde ir como polícias de apito estridente, pronto a furar-nos os tímpanos da liberdade dos gestos… Porque se as paredes podem ser reduzidas a desafios físicos e a máquinas de esticar os limites das fibras musculares, também podem ser outra coisa que transcende o simples desafio equacionado num número.

As paredes podem ser palco de demónios internos, jogo de xadrez contra si próprio jogando com as pretas o medo, cave escura e varanda sobre abismos em nós, espalhafatos de circo ou silêncios de velório na presença do morto que poderemos vir a ser, consultórios de psicanálise vertical que não se pagam, trombetas que acordam dos seus profundos sonos heróis que desconhecíamos ou bestas feitas de medo, inveja e coisas negras…

Quando ao final do dia, no lusco-fusco de um Sol que se afundou no Atlântico, saímos por cima da parede do Espinhaço, é como se viéssemos de um teatro onde estivemos a representar o nosso verdadeiro papel. E o Sol a Poente é o baixar do pano sobre nós próprios. Os dias no Espinhaço são sempre dias especiais.

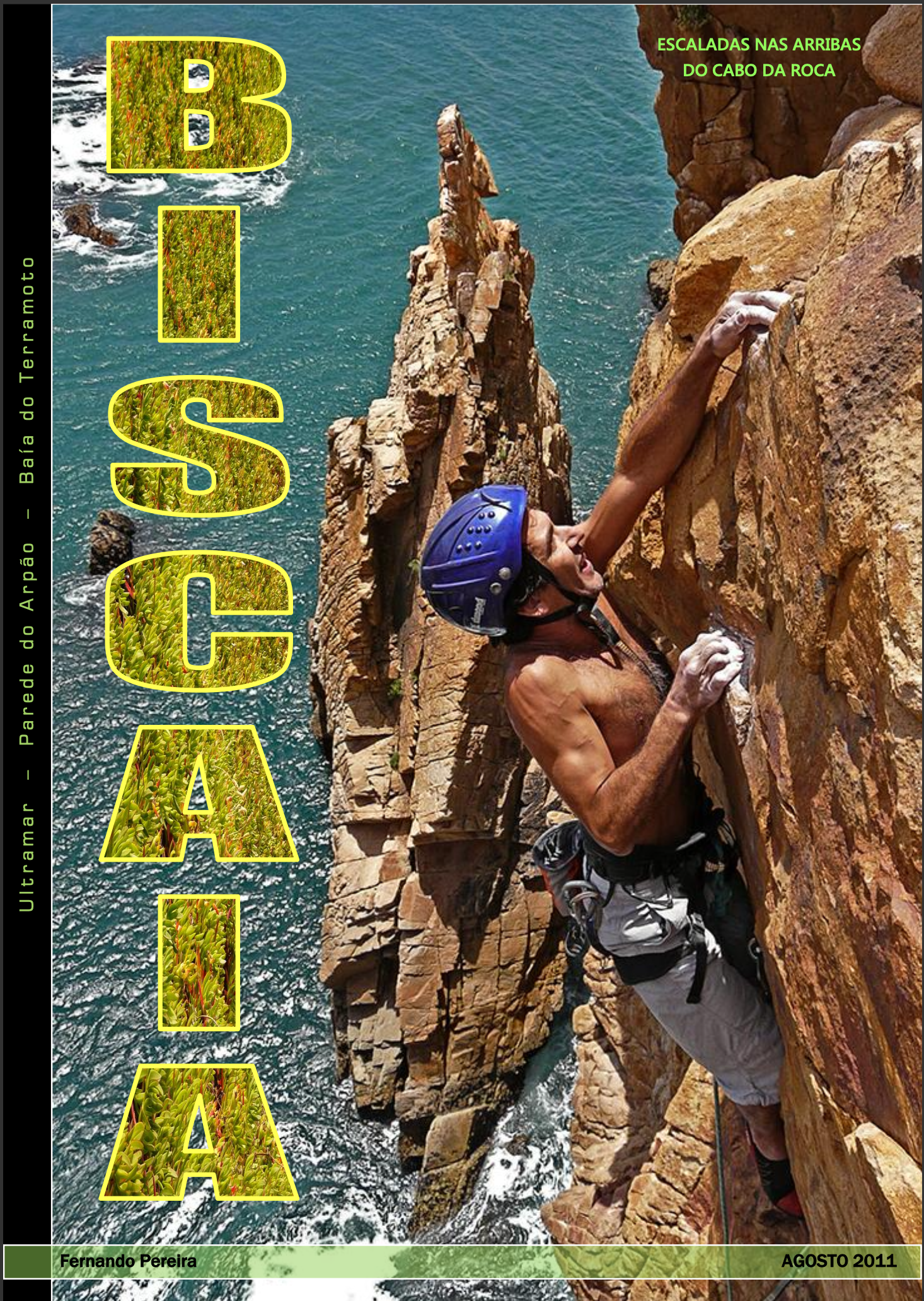

Biscaia

excerto de ESCALADA NA BISCAIA - CABO DA ROCA de Fernando Pereira

As arribas da costa do Cabo da Roca reúnem, no seu conjunto, vias de grande qualidade e simbolismo histórico para a escalada em Portugal. Consta que serão perto duns 15 sectores ou aglomerados de sectores que se estendem desde a Praia Grande à praia do Abano, contando mais de 200 vias.

Este guia dá a conhecer um pequeno núcleo de sectores, discretamente recolhidos na proximidade do lugar da Biscaia (Malveira da Serra – Cascais).

À falta de melhor topónimo, ficou com o nome desse lugar próximo - Biscaia – e apresenta-se aos potenciais visitantes como uma oportunidade para dominar mais alguns recursos técnicos úteis, dadas as especiais características das suas vias.

Destas características destacam-se os inícios de via em reuniões suspensas sobre o mar e algum do granito mais caprichoso destas escarpas, numa abundância e variedade de formas de presas e possibilidades de proteção natural, de que resulta acima de tudo, uma escalada de desfrute.

Espera-se com a divulgação deste sítio, desvendar mais um pouco do que existe nesta parte da Costa, guardiã de vias tão antigas como, injustamente, pouco frequentadas.

Seria uma aposta ganha se esta publicitação servisse de encorajamento ao simples ato de escalar as vias para que não ocorra uma infundada falta de procura e para que o (pouco) equipamento fixo não acabe apodrecido antes de ter servido a mais alguém do que um punhado de cordadas pioneiras.

Escalar as vias da costa do Cabo da Roca será isso mesmo, um tributo auto reversível, de assumir a promoção dum pouco da história da escalada como capital e património de experiência cultural positiva.

Tal como os demais sectores costeiros, a Biscaia não comporta muitos visitantes, e muito menos dos que têm feito deles depósitos de resíduos domésticos ao longo dos anos. Seria bom que se conseguisse reduzir esta tendência, com os meios que nos forem possíveis.

Agradece-se a ajuda de todos os que através das suas contribuições com a Sociedade de Equipadores Anónimos possibilitaram a colocação de argolas e a todos os que colaboraram na criação de vias.

Dedica-se este guia aos poucos escaladores encantados, que, seguramente desde há mais de três décadas, viram nestes declives, de aspeto à partida tão pouco promissor, ilusão, donde extraíram e partilharam linhas de carácter e beleza, em particular a alguém que uma vez escreveu ―! Variem, Porra!